Goals

During this lab you will:

- Practice building and running programs on the Pi using the cross-compile dev tools and

xfelbootloader. - Construct simple breadboard circuits using LEDs, resistors, and buttons.

- Explore the assembly code for the blink and button programs.

Prelab preparation

To prepare, please do the following before coming to lab:

- Be up to date on recent lecture content: RISC-V assembly, GPIO

- Reading to do ahead of lab:

- Read this SparkFun tutorial on using a breadboard. Pay special attention to the section labeled "Anatomy of a Breadboard" to learn about the internal connections.

- Review course guides on:

- powering the Pi

- using the xfel bootloader to send programs to the Pi

- one page of RISC-V assembly

- Organize supplies to bring with you:

- Bring your laptop with full battery (and cable/charger if needed)

- If you have access to a multimeter, bring it along.

Lab exercises

0. Pull lab starter code

Before starting a new lab or assignment, cd to your local mycode repo and pull in the lab starter code:

$ cd ~/cs107e_home/mycode

$ git checkout dev

$ git pull code-mirror lab1-starter

Your repo should now be on the dev branch and has a subfolder named lab1 containing the lab starter files.

1. Inventory your kit

You will receive your parts kit when you arrive at lab. Open it up and check it out! Unwrap and discard the packaging bags and wrappers. Identify what each component is and compare to the kit inventory to ensure your kit is complete. If you are missing any parts, ask us for replacements.

The handy plastic box is so you can take the kit on the go. The top of the box has a blank label for you to decorate with your name so that you and your box stay united. Plan to bring your entire parts kit to every lab.

2. Power up Pi and use xfel to converse

Start with our course guides to acquaint yourself with your new BFF.

- Guide: powering the Pi

- follow instructions to connect your Pi to power

- Guide: xfel bootloader

- follow steps to

- peek and poke to turn on the blue act LED

- use

xfelcommands to load and execute a program - use

mango-runas a bootloading convenience

- follow steps to

If you run into any snags or have questions, be sure to ask for help.

Change to the directory $CS107E/bin and use the following commands to examine the size and data in the blink-actled.bin program file:

$ cd $CS107E/bin

$ ls -l blink-actled.bin

$ hexdump -C blink-actled.bin

How many bytes of data are in the program file? How many instructions does this correspond to? What does this data represent?

Reset your Pi now. Use xfel ddr d1 to initialize the memory controller and xfel hexdump to display the contents of the 200 bytes of memory at address 0x40000000. This is the initial contents of memory after the Mango Pi has reset.

$ xfel ddr d1

$ xfel hexdump 0x40000000 200

Reset your Pi again and repeat the same commands above. Compare the memory contents from xfel hexdump in each case. Are the initial contents of memory the same after every reset or does it vary? Does the memory appear to be filled with zeros, random/uninitialized garbage, or is there some pattern to the values?

Use xfel write to copy the blink-actled.bin program to the Pi's memory at address 0x40000000. Use xfel hexdump again to see the updated contents of memory.

$ xfel write 0x40000000 blink-actled.bin

$ xfel hexdump 0x40000000 200

How have the contents of the memory on the Pi now changed? What is the data and how does it relate to the contents of the blink-actled.bin file?

Use xfel to execute the loaded program.

$ xfel exec 0x40000000

You should be rewarded with a blinking blue act LED on the Mango Pi board. You have just bootloaded your first program! To stop execution, reset your Pi.

Using mango-run

Every time you run a new program, you would repeat these same xfel commands (ddr, write, exec) so we packaged them into a simple script mango-run to give you one-stop shopping. Try it out now:

$ mango-run # no argument, report if Mango Pi connected

$ mango-run blink-actled.bin # bootloads program given as argument

What happens if you try to mango-run a second time

after the bootloader has already loaded a program? Why does that happen?

To halt the current execution and start over, reset the Pi. The Pi will restart into FEL, ready to receive a new program.

3. Make LED circuit on breadboard

Grab the breadboard from your parts kit. You are going to use it to wire up a simple circuit. First, be sure you understand how the breadboard is internally constructed. Which holes are connected to which other holes? How are the power and ground rails connected? Review the section "Anatomy of a Breadboard" in the SparkFun tutorial on breadboard from the pre-lab.

Test a few points on the breadboard to confirm the internal connections. Get out your multimeter if you brought one or borrow one of the shared lab multimeters. Grab two male-male jumpers (any colors) from the bin of jumpers in the lab room. Choose two neighboring holes along one of the power rails and plug one end of each jumper into the holes. Confirm these holes are connected by applying the multimeter leads to the free ends of the jumpers and testing for continuity. Now move the jumpers around to different positions on the breadboard (for example, two holes within same row or same column or one hole in each power or ground rail) as you continue testing for continuity. Sketch out a road map of which holes are connected and which are not.

You are going to wire up a simple circuit to light an LED. You'll need an LED and a 1K resistor from your kit. A resistor's value is indicated by the sequence of colored bands. (See this Sparkfun tutorial on resistors for help on decoding the bands and bookmark this color code calculator.) What are the band colors for 1K? Find a 1K resistor in your kit and use the multimeter to measure the resistance to confirm the value.

Make a circuit on your breadboard for the LED. An LED has a directionality – the longer lead is the anode and the shorter lead is the cathode. The voltage from anode to the cathode should be positive. If the polarity of voltages are switched, the LED will not light up. The LED also needs a current-limiting resistor otherwise it can literally blow up in a fiery, smoky extravaganza! A resistor has no directionality and it can be placed ahead or behind the LED in the circuit.

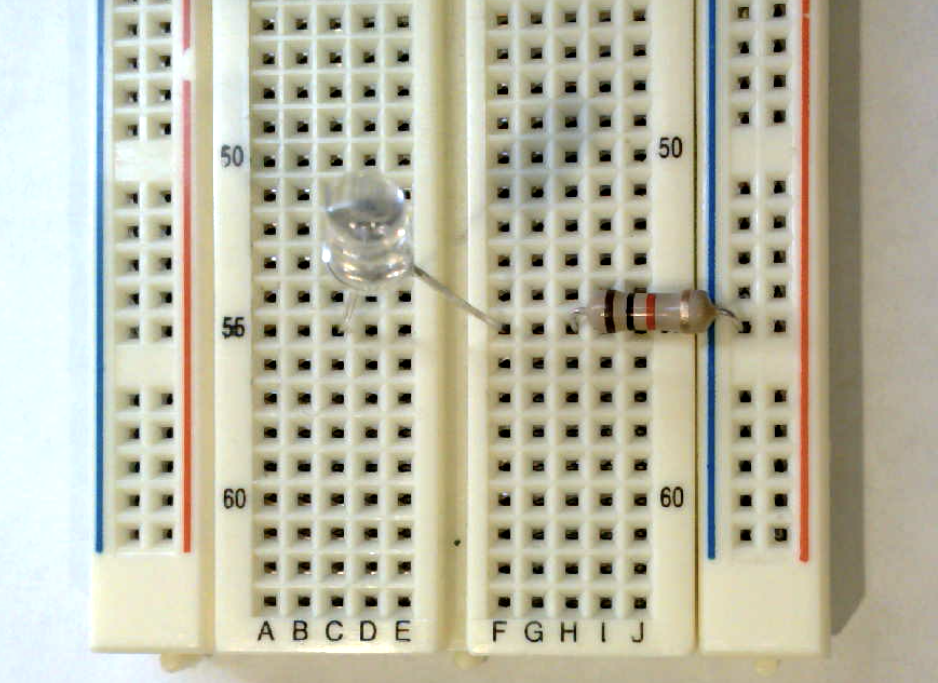

In the photo below, the cathode of the LED connects to the resistor which connects to the the blue ground rail. The LED itself crosses over the middle of the breadboard. (click photo to enlarge)

We are just playing with this circuit in lab, so we won't worry about making things tidy and secure. When installing a more permanent circuit such as for assignment 1, you can use pliers to make a clean bend in the legs and snip the ends with a cutter so that each component sits neatly on the breadboard.

To light the LED, you need to apply power to the anode and complete the circuit by connecting the cathode to ground. The power and ground will come from the header pins on your Mango Pi.

Follow these steps:

- First, disconnect your Pi from power.

Danger Always take care to cut power to the Pi before you fiddle with the wiring. If you leave it plugged in, power is flowing and all wires are live, which makes for a dicey situation. An accidental crossed wire can a short circuit, which could fry your Pi or make your laptop disable the USB port.

-

Pick out two female-male jumpers from your kit, one red and one black. You'll use the red for power and black for ground. Of course, electrons don't care about colors, but adopting good conventions will helps us humans more easily trace and debug our circuits.

- Your kit includes a printed pinout refcard that you'll want to keep handy, grab it now. We also have a command-line version for that retro ascii art feel. Try it out!

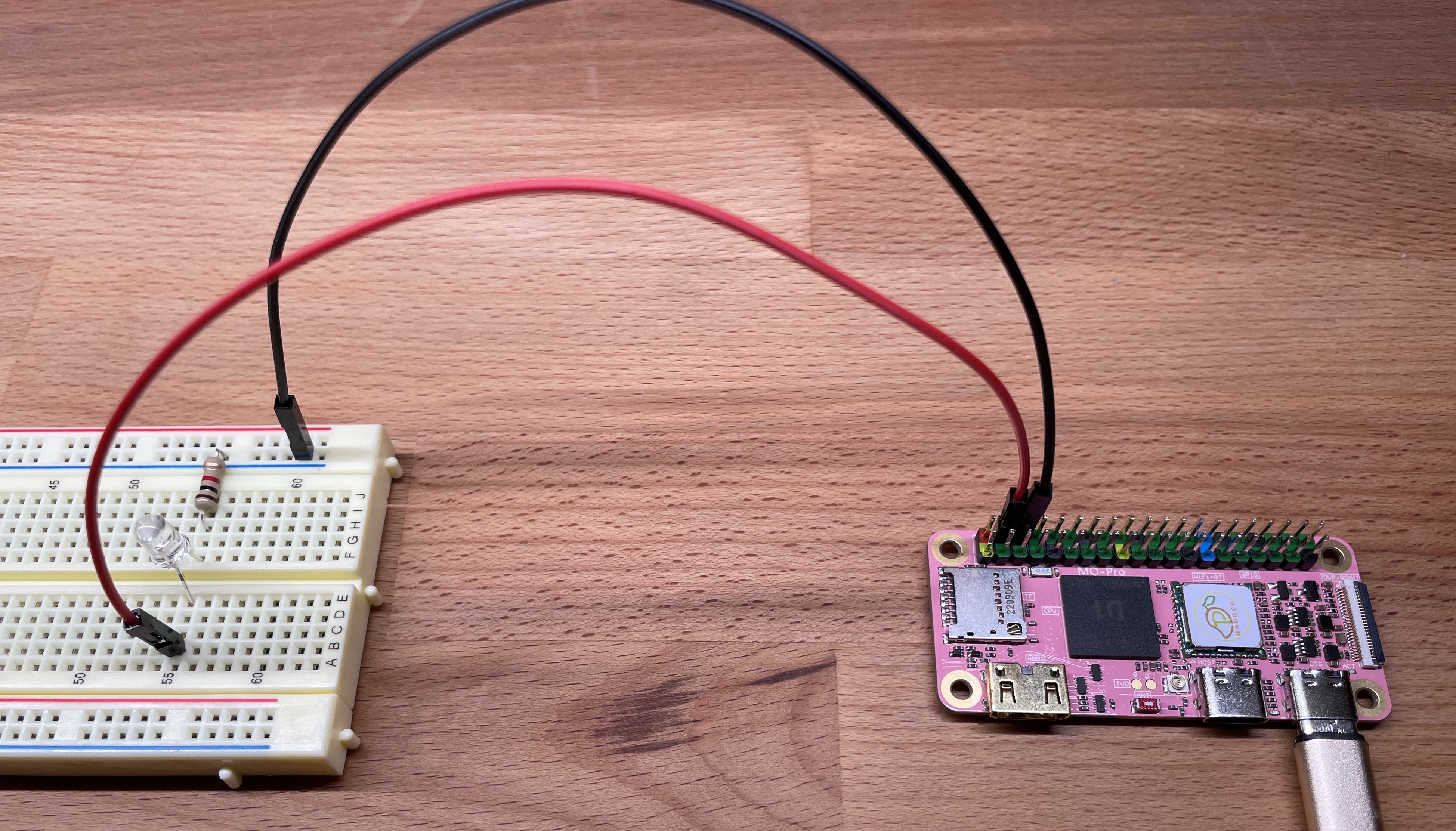

$ pinout.pyOrient your Pi so that the 40-pin header is in a vertical column on the right edge to match the pinout diagram. Identify a 5V power pin and a GND pin on the header of the Mango Pi. Connect the female ends of the jumpers to the Mango Pi: black to ground and red to power.

-

Plug the male ends of the jumpers into the breadboard: black jumper to the blue ground rail and red jumper to the anode of the LED. (click photo to enlarge)

- After double-checking that your circuit wiring is correct, you're ready to apply power. Power up the Pi and the LED on the breadboard should light.

While the LED is lit, make the following measurements with the multimeter.

- Measure and record the voltage across the resistor

- Measure and record the voltage across the LED

Apply Ohm's law to these measurements to calculate the current flowing through the LED.

If you substitute a 10K resistor in place of the 1K, how will this change the rate of current flow? How does it change if you connect to a 3.3V power pin instead of 5V?

What effect do these changes have on the brightness of the LED? Do some comparisons with your tablemates. Have one of you swap and compare the brightness of the changed circuit to the original and see the effect with your own eyes. (Be sure power is disconnected while fiddling with the wiring!)

You are ready to answer the first check-in question. 1

4. Execute blink program

You want to run blink program from lecture which blinks a LED connected to gpio PB0. Look on your pinout card and find the pin labelled PB0. You can also identify a pin by giving an optional argument to pinout.py:

$ pinout.py PB0

Now that you know which pin is PB0, re-configure your breadboard circuit to connect PB0 to the anode of the LED.

The blink subfolder of lab1 contains the code for the blink program shown in lecture. Change to that folder and build the blink program using these commands:

$ cd lab1/blink

$ riscv64-unknown-elf-as blink.s -o blink.o

$ riscv64-unknown-elf-objcopy blink.o -O binary blink.bin

The riscv64-unknown-elf-as command assembles the RISC-V instructions in blink.s into an "object

file". The assembler takes in assembly instructions (text) and translates to machine-encoded instructions (binary). In addition to the encoded instructions, the object file includes some extra data we don't need – we just want the

program. The command riscv64-unknown-elf-objcopy extracts just the raw binary program of instructions into a file

blink.bin.

Use the mango-run command to send the program to the bootloader:

$ mango-run blink.bin

xfel ddr d1

Initial ddr controller succeeded

xfel write 0x40000000 blink.bin

100% [================================================] 36.000 B, 21.542 KB/s

xfel exec 0x40000000

Running the blink.bin program on the Pi should pulse gpio PB0 which is connected to the LED on your breadboard.

5. Study blink program (RISC-V assembly)

Below is the blink program that from lecture. This code is available in the file lab1/blink/blink.s and also reproduced below.

lui a0,0x2000 # a0 holds base addr PB group = 0x2000000

addi a1,zero,1 # a1 holds constant 1

sw a1,0x30(a0) # config PB0 as output

loop:

xori a1,a1,1 # xor ^ 1 invert a1

sw a1,0x40(a0) # set data value of PB0 to a1

lui a2,11000 # a2 = init countdown value

delay:

addi a2,a2,-1 # decrement a2

bne a2,zero,delay # keep counting down until a2 is zero

j loop # back to top of outer loop

If there is anything you don't understand about this program, ask and discuss it with others.

Identify the lui instruction that inits the countdown. The value determines the number of loop iterations in the delay loop. The "load upper immediate" operation loads into the upper 20 bits of the destination register, effectively left-shiting the immediate by 12 positions. The instruction lui a2,11000 initializes the countdown to 11000 << 12 which is roughly 45 million.

Edit the assembly instructions to halve the countdown value; this should make the delay half as long. Rebuild and run the program to see that it now blinks twice as fast.

It is a multi-step process to modify the program and re-run it:

- In your text editor, edit

blink.sand save changes. (pro-tip: do not exit editor, leave open and switch to other terminal) - Re-build

blink.bin(build commandsasandobjcopy) - Reset the Pi (can either unplug and replug OTG or press small reset button on side of Mango Pi board)

- Bootload and execute

mango-run blink.bin

Make sure you understand why each step is necessary. Show off your working edit-build-run cycle when you check-in with us. 2

Experiment with changing the number of loop iterations (i.e. the countdown value) until you observe a blink rate of roughly 1 second on and 1 second off. Review the assembly and count the number of instructions executed within each loop iteration. Combine these numbers to calculate an estimate of how many instructions per second the Mango Pi is executing. Compare your estimate with your tablemates – does the measured rate mostly jibe with the stated clock speed (1Ghz)? You can now answer this check-in question3.

Toward a productive workflow You will be spending much quality time with your editor and terminal and will want to develop an efficient and productive workflow. Pay attention to speed bumps and awkwardness and consider what tools you have that can help streamline your process. For example:

- Learn how to use tab-complete and history as shortcuts to avoid (re)typing of commands and filenames. If you don't yet know about these features, ask a peer to show you or do a web search for a tutorial.

- Don't close out your editor each time you need to return to your shell; keep open multiple windows/tabs and use keyboard control to quickly switch between them.

- Organize your screen for visibility of all essential content, don't force yourself to hunt through scattered and overlapping windows.

- Longer term: avoid the overhead of reaching for your mouse and instead learn how to leverage key bindings and macros, so you can keep your hands on the keyboard and stay in programming flow state.

- "The single biggest productivity slowdown I see in stanford undergrads (grads too) is the slow, laborious use of taking their hand off a keyboard, moving a mouse, clicking, switching screens, clicking on something else, switching back, etc. You don't realize how much this slows you down you until you watch someone who writes code well and compare their fluent flow to your plodding agrarian lifestyle. Any time you move the mouse, you're not doing work. Do what you can to stop this." –Dawson Engler

6. Add a button

The final lab exercise is to study the button program and build a circuit to test the program.

This button program is in the file lab1/button/button.s. It uses two gpios: PB0 configured as an output and connected to an LED and PC0 configured as an input and connected to read state of a push button. The initial instructions of the program turn on the LED connected to PB0 and there after it goes into a loop which reads the value of PC0 and turns off the LED when the button is pressed.

lui a0,0x2000 # a0 holds gpio base addr = 0x2000000

addi a1,zero,0x1 # a1 holds constant 1

sw a1,0x30(a0) # config PB0 as output

sw a1,0x40(a0) # turn on PB0

sw zero,0x60(a0) # config PC0 as input

loop:

lw a2,0x70(a0)

and a2,a2,a1

beq a2,zero,off

on:

sw a1,0x40(a0)

j loop

off:

sw zero,0x40(a0)

j loop

Challenge yourself to understand what each line of code accomplishes and why it works as expected. We annotated the first few lines to get you started, add your own annotations as you figure out each line. Have the D1-H user manual handy for looking up information about the GPIO peripheral and bookmark our one-page guide to RISC-V instructions.

Here are a few questions to test your understanding.

- What information is stored in the peripheral registers at addresses

0x02000060and0x02000070? - What value is being tested by the

beqinstruction? - Will the LED on or off when the program starts?

- What will be the value of

PC0when the button is not pressed? When the button is pressed?

Once you understand how the code operates, you are ready to make the button circuit.

Grab a pushbutton from your parts kit. The button has four legs, which are partitioned into two opposing pairs. The legs within a pair are always connected to one another. When the button is pressed, all four legs become connected. Wiring a connection from a leg to one in the opposite pair will read as open until the button is pressed. Your first task is to work out which leg pairs are always connected and which only become connected when the switch is closed. How the legs are wired is not obvious! One way to experimentally confirm is using the multimeter to test for continuity across each pair of legs. Once you understand how the legs are connected, position the button on the breadboard so it can act as a switch.

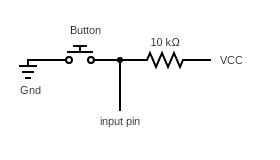

You will connect an input pin from the Pi into the button circuit to read the button state (pressed or not pressed). The default voltage of a gpio pin operating in input mode is in a "floating" state, it might read high, it might read low, the value can even change unpredictably. We must intentionally pull the pin to a known voltage to establish a reliable reading. The button program above is written expect that the button state is initially high and goes low when pressed, so we need to make the default state high. We can do this by connecting the input pin to the power rail through a 10K resistor to "pull up" the line. This causes the gpio to read high by default when the button is not pressed. Pressing the button grounds the circuit and the gpio will then read low. Sparkfun has a nice tutorial on the use of pull-up resistors for more information.

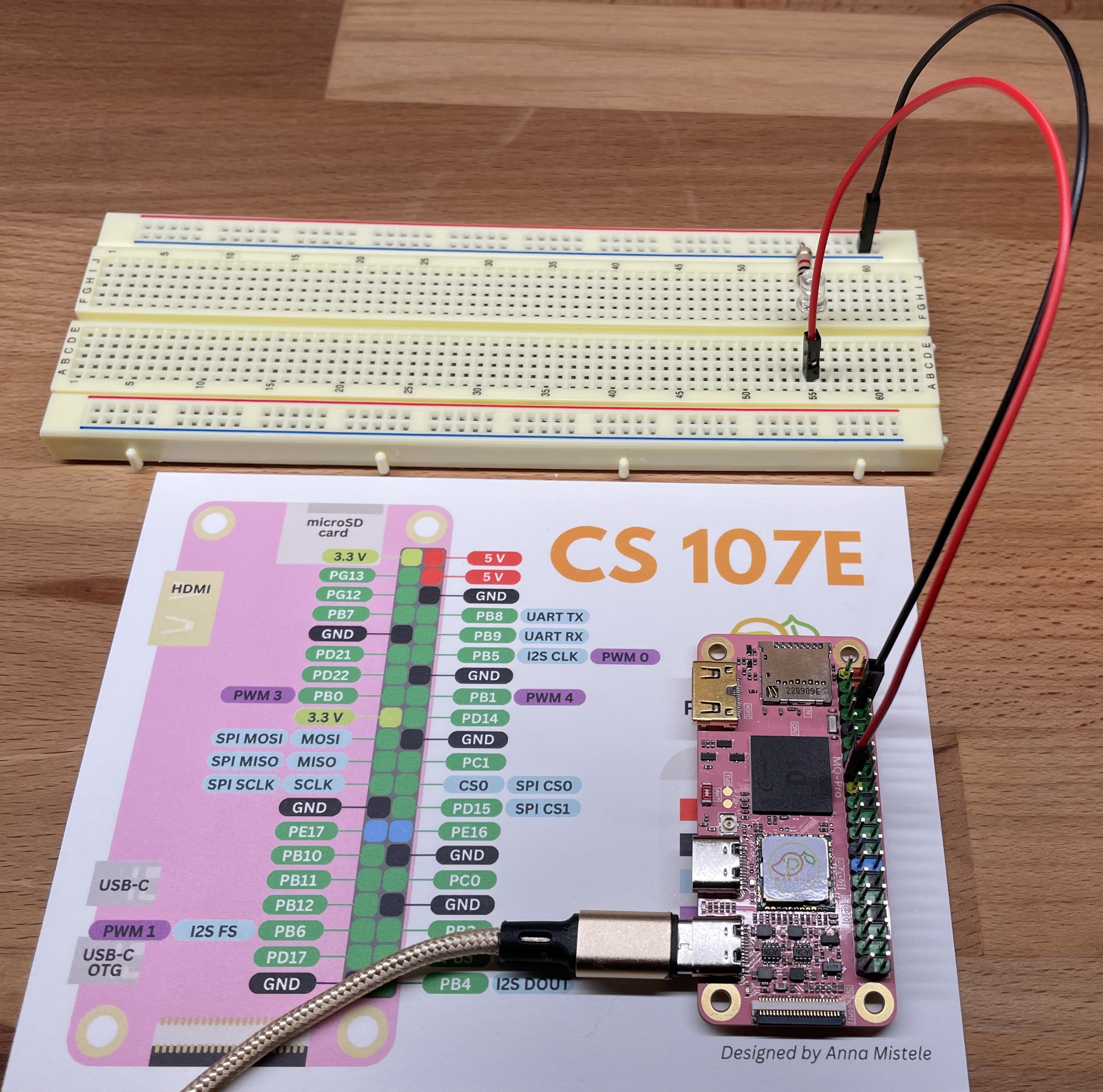

Below is the schematic for a button connected to a pull-up resistor. The input pin will read high while switch is open (button unpressed) and low when switch is closed (button pressed).

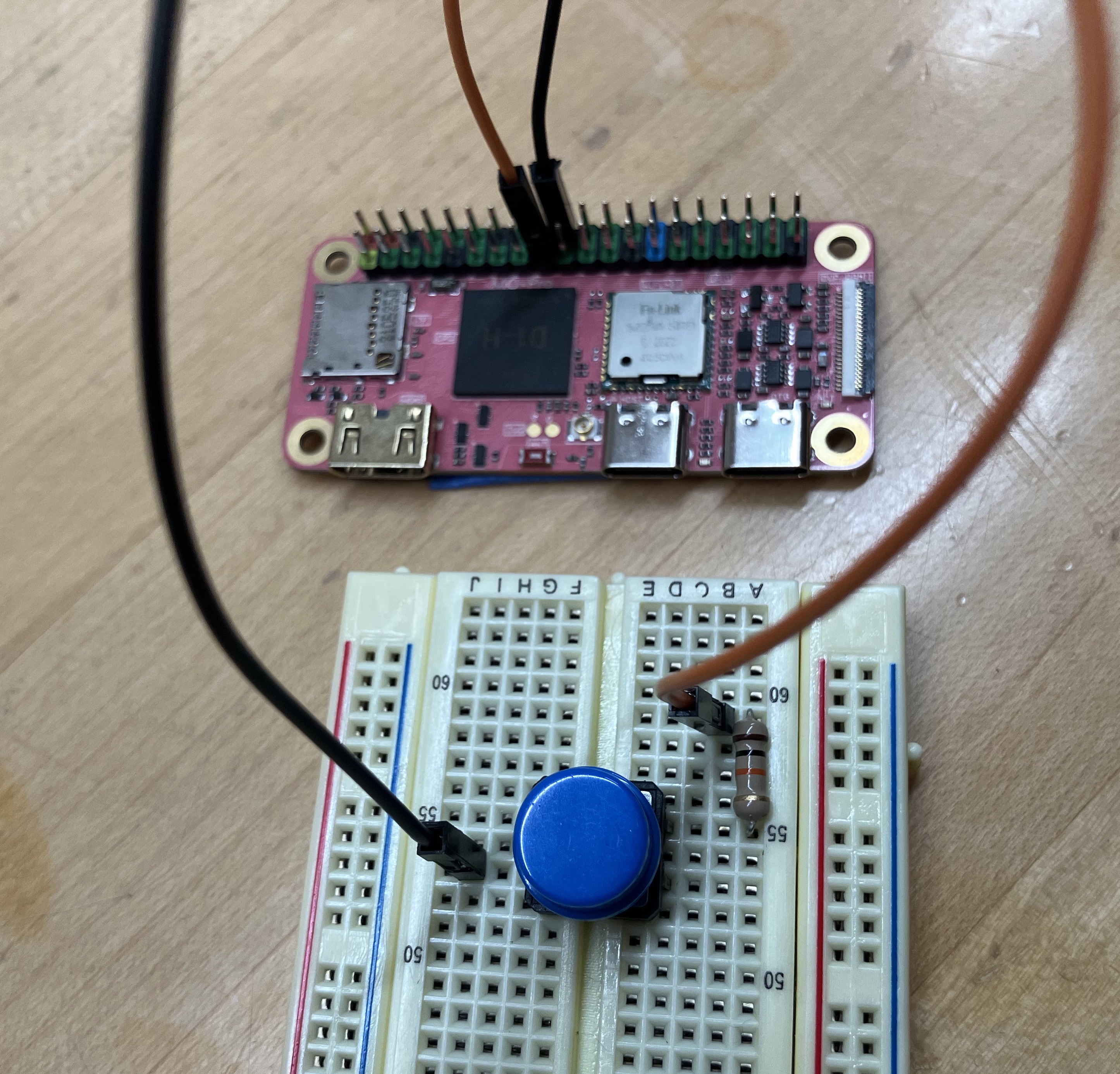

Below is a photo of a partial circuit corresponding to the schematic above. VCC (3.3V) and ground are connected to the Pi, R1 is a 10K resistor uses as a pull-up. Add this partial circuit on your breadboard (keep the existing connections for the PB0 LED intact as well).

In the photo above, we used an orange jumper to connect 3.3V on Pi to one end of the pull-up resistor, the other end of the resistor is connected to the northeast leg of the button. We used a black jumper to connect the southwest button leg directly to ground on Pi. Pressing the button completes the circuit and power will flow from VCC through the resistor through the closed button and eventually to ground.

Be sure you understand why the resistor is needed! If power was connected directly to the button leg, pressing the button would form a short between power and ground that could damage your Pi. Ouch!

Double-check your wiring! Before powering up your circuit, "read" it over to confirm it correctly models the schematic. Choosing jumper colors that follow consistent conventions (e.g. orange for 3.3V power, black for ground) can help with readability.

The circuit in photo is not yet complete – it is missing the connection to read the button state. Review the schematic to identify where the input pin connects into the button circuit. The input point is chosen such that the input will read high in the starting state and read low when the button is pressed. Use the pinout to find gpio PC0 on the Mango Pi header. Add a jumper from PC0 to the input and your circuit is complete.

Your breadboard should have the previous circuit of LED connected to PB0 and the additional button circuit connected to PC0. You are now ready to power it up and build and run the button program. Time for another round of riscv64-unknown-elf-..., uh, what was that again? Let's add another useful tool to your bag of tricks: make. A Makefile can be used to list the commands needed to build and run the program and allows you to skip re-typing them again and again. Next week's lab will have an exercise on exploring make, for now, you can take it on faith that we have provided a Makefile to use. Use the command make run as a shortcut for building and running a program on the Mango Pi. Try it out now!

$ make run

riscv64-unknown-elf-as button.s -o button.o

riscv64-unknown-elf-objcopy button.o -O binary button.bin

mango-run button.bin

If the LED is on at start and turns off when the button is held down, you've got it all right! You're ready to answer the final check-in question4.

Check in with TA

Be sure to hand in your check-in sheet before leaving lab. We encourage you to touch base with us along the way rather than batching up your questions at the end5. Remember the goal of the lab is not to rush through to finish fastest; it's to work through the material and build understanding.

Clean all the things: Please return tools and supplies to their place, discard any trash, and straighten up the tables and chairs. Our lab room is our home, let's work together to keep it a tidy and welcoming place.

Lab 1: Getting to know your Mango Pi

Circle lab attended: Tuesday Wednesday

Fill out this check-in sheet as you go and use it to jot down any questions/issues that come up. Please check in with us along the way, we are here to help!6

-

How much current flows through the LED with a 1K resistor connected to 5V? With a 10K resistor connected to 3.3V? ↩

-

Show off the workflow you are using to edit/compile/execute a program on the Pi. Everyone should confirm this success individually; this is an important takeaway before starting Assign1. ↩

-

What is your experimental estimate of the rate of instructions per second executed by the Mango Pi? How did you compute it? ↩

-

Show us your annotated version of

button.sand your completed breadboard circuit with button and LED. What is the purpose of the resistor in the button circuit? Why is it needed? How could you re-arrange the button circuit for a pull-down resistor instead of pull-up? How would you need to change the code to match this re-wired circuit? ↩ -

Are there any tasks you still need to complete? Do you need assistance finishing? How can we help? ↩

-

Do you have any feedback on this lab? Please share! ↩