Goals

The goal of this lab is to get you started with interrupts in preparation for your final assignment.

During this lab you will:

- Review the support code for interrupts on the Pi,

- Write code to handle button presses using GPIO event interrupts, and

- Brainstorm possibilities for achieving world domination with your final project.

Prelab preparation

To prepare for lab, do the following:

To prepare for lab, do the following:

- Be up to date on recent lecture content: Interrupts

- Review the interrupt support code we introduced in lecture (all source files in directory

$CS107E/src);interrupts_asm.sassembly instructions to access CSRs for interruptsinterrupts.clibrary module to manage trap_handler, interrupt sources, and dispatch to registered handler per-sourcegpio_interrupt.clibrary module to manage GPIO interrupts and dispatch to registered handler per-pinringbuffer.clibrary module that implements queue as ringbuffer, safe for shared access by one enqueuer and one dequeuerhstimer.clibrary module for countdown timer

- Review the interrupt support code we introduced in lecture (all source files in directory

- Browse our project gallery to gather ideas and inspiration from the projects of our past students.

- Organize your supplies to bring to lab

- Bring your laptop (with full battery charge) and entire parts kit.

- You do not need your PS/2 keyboard for this lab, it can stay home.

- You will need a HDMI monitor to complete these exercises. We have monitors available in lab for shared use.

Lab exercises

Pull lab starter code

Change to your local mycode repo and pull in the lab starter code:

$ cd ~/cs107e_home/mycode

$ git checkout dev

$ git pull code-mirror lab7-starter

Interrupts

1) Review interrupt assembly

In the first lecture on interrupts, we went over the low-level mechanisms. The interrupts module is used to configure interrupts and manage handlers at a global level. The module interface is documented in interrupts.h and its implementation is split into the files interrupts.c (C code) and interrupts_asm.s (assembly). These source files are available in the directory $CS107E/src.

Start by reviewing the interrupts_asm.s file which contains the assembly portion of the interrupts module implementation. Here is a roadmap to the functions:

interrupts_global_disableandinterrupts_global_enable- set/clear machine-mode interrupt bits in the

mstatusandmieCSRs.

- set/clear machine-mode interrupt bits in the

interrupts_get_mepcand others- retrieve CSR values that are needed by the interrupts module

interrupts_set_mtvec- sets the address of the function to execute on a trap

These functions have to be written in assembly because the CSRs can only be accessed by the special csr assembly instructions.

The interrupts_set_mtvec sets the function pointer that will be called to service a trap. The trap function should be declared __attribute__((interrupt("machine"))). Review the gcc documentation on function attributes to learn more. The interrupt attribute changes the function's assembly to include a prolog and epilog that safely enter and exit interrupt processing.

Open https://gcc.godbolt.org/z/fPGdz4MPP in your browser; this is a Compiler Explorer example that shows an ordinary function and three trap functions declared with the interrupt attribute. Look carefully the generated assembly for the trap functions to see what is different.

- When a function completes, where does control flow resume?

- An ordinary function ends with

ret, which resumes execution in the caller at the instruction after the call. The address of that instruction is stored in the registerra("resume address"). - A trap function instead ends with

mret, which resumes execution at the interrupted instruction. The address of that instruction is stored in the CSRmepc("machine exception program counter"). - Talk this over with your tablemates to understand the similarities and differences. Why two distinct mechanisms; why is it not possible to use same for both?

- An ordinary function ends with

- The three trap functions differ in which registers are saved to the stack on entry and restored on exit.

trap_Aspills no registerstrap_Bspillsa4anda5trap_Cspills half of all 32 general-purpose registersra,t0-t6, anda0-a7- Why the difference in which registers are being saved? Why those specific registers are not others?

- How does the memory being used for the stack frame for the trap function relate to the stack memory being used by the ordinary functions?

- If you were to call

backtrace_gather_frames()from within the trap function, what would the backtrace look like?

- If you were to call

You're ready for this check-in question1.

2) Review interrupt dispatch

The C code in interrupts.c implements the bulk of the interrupts module. Start by reviewing the implementation of the trap_handler function. This trap function is installed using interrupts_set_mtvec and will be called for every trap. If the trap was due to an external interrupt, it dispatches to the registered handler. All other trap causes are an unrecoverable fatal exception, so the functions prints an error message and exits with mango_abort.

In our second lecture on interrupts, we reviewed the design that dispatches an event to its associated handler function. The design for dispatch in both interrupts and gpio_interrupt uses an array of function pointers, one per-index. The client who wants to use interrupts implements a handler function and registers it with the dispatcher. The dispatcher stores the client's function pointer in the array at the associated index. When an event occurs, the dispatch invokes the handler function at that index. In the top-level interrupts module, the interrupt source number is the index into the array of handlers. In the gpio_interrupt module, the pin index within the gpio group is used as the index.

There is a neat performance trick that applies here. To identify which gpio pin has a pending event, the dispatcher scans the status registers to find the first bit that is set. If you were implementing that scan in C, you might loop and shift/test each bit individually. A more streamlined version could do fancy bit twiddling, such as Kernighan's bit count algorithm, or employ on a lookup table. Such versions might take tens or even hundreds of cycles.

A better way to implement is to drop down to assembly and leverage bitwise tricks to count leading zeros. We are using the hand-rolled assembly provided by gcc in software (__builtin_clz). Enthusiastic hackers compete to see if they can outperform it. The recently ratified RISC-V Zbb extension adds a clz (count leading zeros) instruction that counts in as few as 3 cycles. (Sadly, the C906 processor in the Mango Pi pre-dates this extension…). Reducing the time it takes to find a pending interrupt from 100 to 3 cycles, (an improvement of 33x!) is a big benefit to every single interrupt. This kind of throughput boost is why instructions like clz exist. Neat!

Test your understanding of interrupt dispatch by reviewing these questions.

- How is a function "registered" as a handler with a dispatcher? How does the dispatcher know which handler to call for a given event? Can there be multiple handlers registered for the same event? If there is no handler registered for a pending event, what will the dispatcher do with the event?

- An

aux_datapointer can be stored with the handler. That pointer is later passed as an argument to the handler when invoked. What is the purpose of anaux_datapointer?

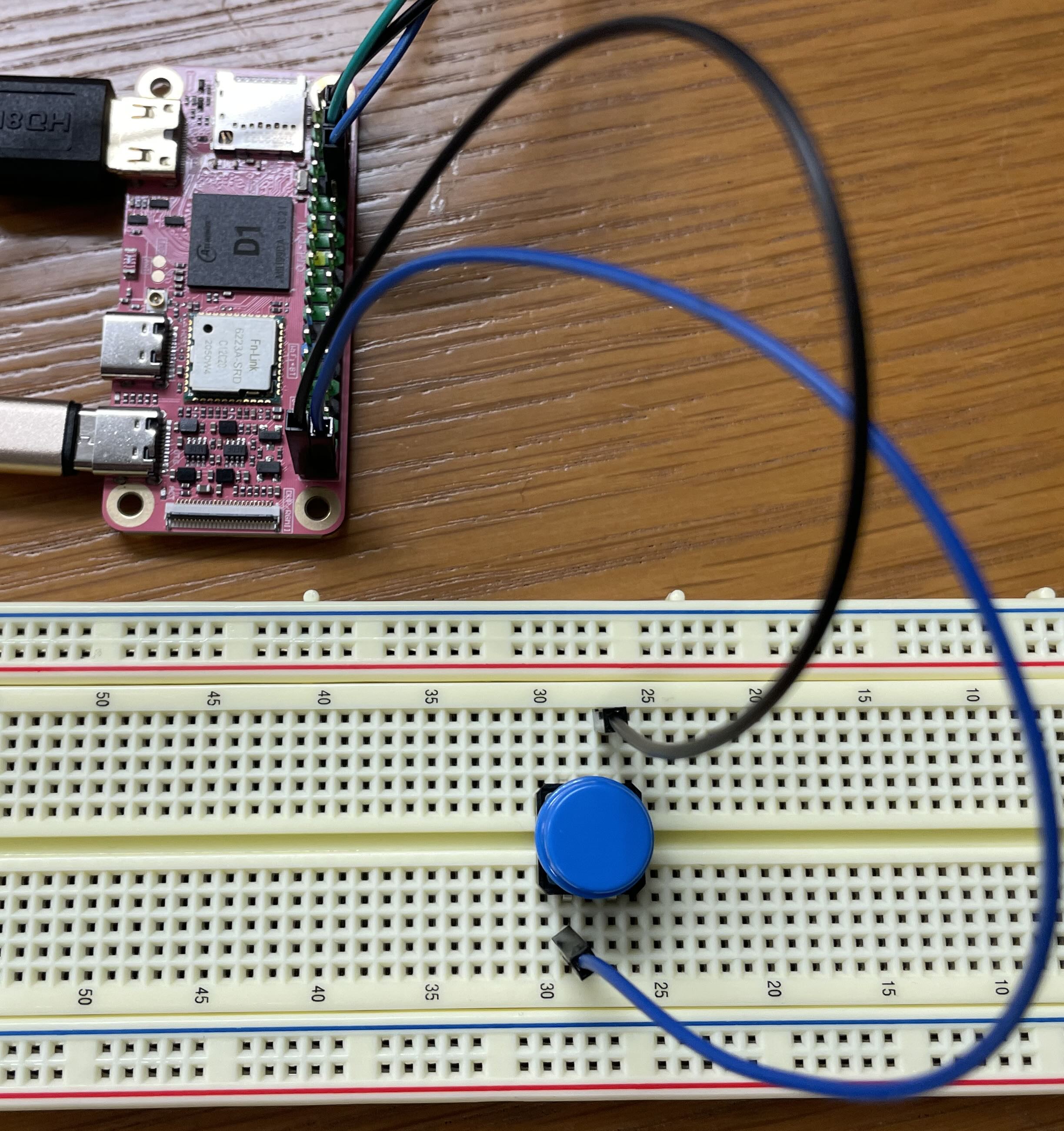

3) Set up a button circuit

Let's execute some code that uses interrupts. Set up a one-button circuit on your breadboard. Connect one side of the button to gpio PB4 and the other side to ground. Connect your Pi to a HDMI monitor.

Back in Assignment 2, we put a hardware resistor in the button circuit to set default state. This time, the code activates the internal pull-up instead. When the button is not pressed, the internal resistor "pulls up" the value to 1. When the button is pressed, it closes the circuit and connects the pin to ground. The value then reads as 0.

Review the code in lab7/button/button.c. In the starting version, main function sits in a loop that calls wait_for_click and then redraws the screen.

Fill in the implementation of the empty wait_for_click function to operate by polling. It should:

- Wait for a falling edge on the button gpio, i.e. loops calling

gpio_read()until observe a transition from 1 to 0. Review the loops you used to wait inps2_readif you need a refresher.

Compile and run the program. The program sits and waits for you to click the button. When you do, the message is printed and the screen redraws to show the incremented count. This version of the program is either redrawing OR waiting for a click. While waiting for a button press, the screen redraw is paused. While redrawing the screen, no button presses are detected. Ideally, we want the program to do both tasks concurrently.

- If you click the button multiple times in quick succession, some of the presses are missed. You get neither a printed message nor a screen redraw and these clicks are not included in the count. Why does that happen?

You'll note that redrawing the screen is quite slow. If we were to speed up the drawing, it would cause us to miss fewer events, but it doesn't fundamentally solve the problem. Interrupts are the better solution!

4) Write a button handler

Remove the call to wait_for_click from the loop in main. Compile and re-run. The program now repeatedly redraws the screen. If you click the button, there is no response. The program never calls wait_for_click and won't observe any change in the GPIO pin; it's 100% occupied with drawing.

You are now going to rework the program to process those button clicks as interrupts.

Start by reviewing the documentation for the library modules you will use:

- gpio_interrupt.h

- Gpio interrupts module

- interrupts.h

- Top-level interrupts module

There are multiple steps to set up an interrupt and coordination is across two modules: gpio_interrupt for gpio-specific configuration and top-level interrupts module for global state.

- Define your handler function to be called on a button click

- The function prototype is

void handle_click(void *aux_data). We are not yet using theaux_dataargument, but prototype must exactly match the standard handler prototype in any case. - Look in

gpio_interrupt.hto find the function used to clear an event. A handler function must clear the event, otherwise it will continuously re-trigger. - In your handler, increment

gCountand output a messageuart_putstring("[YOUR-NAME-HERE] has interrupt mojo!")

- The function prototype is

- Extend

config_button()to add a gpio interrupt for button event following the steps below:- add these steps to the end of the function, after setting to input and activating the pull-up

- call

gpio_interrupt_init()to initialize the gpio interrupt module - call

gpio_interrupt_config()to configure the button event trigger- Clicking the button generates a falling edge (negative edge) event. Pass true for

debounce.

- Clicking the button generates a falling edge (negative edge) event. Pass true for

- call

gpio_interrupt_register_handler()to register your handler function- Pass

NULLforaux_data; the handler does not use the argument.

- Pass

- call

gpio_interrupt_enable()to enable the button interrupt

- Edit code in

main()to set up global interrupts- call

interrupts_init()to initialize the global interrupt system (do this once at very start of program) - call

interrupts_global_enable()to turn on the "global switch" (final step, after all pieces configured and ready)

- call

The order that you do these operations is important: think carefully about each action, revisiting the lecture slides/code if you need to. Talk this over with your tablemates and ensure that you understand what each step does and why it's necessary.

Compile and run the program. If you have done everything correctly, the program continuously redraws as before, but now whenever you click the button, the click count increments and a message prints in your terminal to congratulate your prowess. You get the best of both worlds: your long-running task can be written as a simple loop, yet the system is immediately responsive to input.

Once you have it working, go back and intentionally make various errors, such as doing steps out of order, forgetting a step, or doing a step twice. Seeing the observed consequences of these mistakes now may help you to identify them in the future.

Some things to try:

- What error results if you try to register a gpio interrupt handler before initializing the gpio interrupts module?

- What error results if you try to init the interrupts module more than once?

- What error results if the handler function does not clear the event?

- What changes if you set

debounceto false when configuring the button interrupt?

Change the code back to the correct configuration before moving on.

You're ready for another check-in question2.

5) Coordinate between main and interrupt

You want to change the program to redraw once in response to each button click and otherwise wait quietly rather than continuously redraw. This requires that the interrupt and main code share state.

Edit the code within the loop in main to only call redraw if the count of clicks has incremented past the last redraw, i.e. gCount is higher than count in local variable drawn.

The count of clicks is stored in the global variable gCount. The handler increments it and the main reads the value and compares to saved count. gCount is not currently declared volatile. Should it be? Why or why not? Can the compiler tell, by looking at only this file, how control flows between main and the interrupt handler? Will the compiler generate different code if volatile than without it? Will the program behave differently? Test it both ways to confirm what (if any) is the consequence of not declaring the gCount variable as volatile. You are ready to answer this check-in question3.

6) Use a ring buffer queue

Watch carefully as the program executes and you'll note that every click is detected and counted, but the count of redraw iterations is not one-to-one with those updates. Multiple clicks can occur while the program is occupied in redraw before the main loop gets around to next checking the value of gCount.

To track all updates and process each one by one, we can use a ring buffer queue to communicate updates from the interrupt handler and main. The handler function will enqueue each update to the ring buffer and main will dequeue each update . Because the queue stores every individual update posted by the interrupt handler, we can be sure that we never miss one.

How to rework the code:

- Review the ringbuffer.h header file and source file ringbuffer.c to see the provided ring buffer queue. The ringbuffer is a sequence of integer values implemented as a circular queue.

- In the

mainfunction, declare a variable of typerb_t *rband initialize with a call torb_new. - When calling

gpio_interrupt_register_handler, change to pass therbpointer asaux_data. - Change your click handler function to receive

rbpointer asaux_data, i.e. cast theaux_datatorb_t *. Add the updated value ofgCountto the ring buffer by callingrb_enqueue. - Edit

mainto userb_dequeueto retrieve each update from the queue. Remove the previous code comparinggCountto saved count and instead check if the ring buffer is non-empty to detect there is a pending update to draw.

Make the above changes and rebuild and run the program. It should now redraw the screen once for each button press in one-to-one correspondence, including patiently processing a backlog of individual redraws, one for each click made in fast succession.

When you're done, take a moment to verify your understanding:

- With this change, it is no longer necessary for

gCountto be declaredvolatile, not doesgCountneed to be global (i.e. could declare as static within the handler function). The ring buffer is also not a global variable; we useaux_datato pass it from main to the interrupt handler. What is the benefit to limiting scope and visibility in this way over using a global variable? - The clever design of the ring buffer provides safe concurrent access for one reader and one writer. Review the code in

rb_enqueueandrb_dequeue. Trace what happens if execution is midway throughrb_dequeuewhen an interrupt fires and the handler function makes a call torb_enqueue. Confirm that the updates to the ring buffer from enqueueing the element won't cause problems for the dequeue operation when it resumes. - Why might you want the handler to enqueue an update and return instead of doing the actual task (e.g. redraw) directly in the handler?

You're ready for the final check-in question 4.

Project brainstorm and team speed-dating

Visit our project gallery to see a sampling of projects from our past students. We are so so proud of the creations of our past students – impressive, inventive, and fun! You'll get started in earnest on the project next week, but we set aside a little time in this week's lab for a group discussion to preview the general guidelines and spark your creativity about possible directions you could take in your project. If you have questions about the project arrangements or are curious about any of our past projects, please ask us for more info, we love to talk about the neat work we've seen our students do. If you have ideas already fomenting, share with the group to find synergy and connect with possible teammates. Project teams are most typically pairs, although occasionally we have allowed solo or trios by special request.

Check in with TA

The key goals for this lab are to leave with working code for client use of interrupts and feel ready to start on Assignment 7. 5

Lab 7: Mango Pi, Interrupted

Circle lab attended: Tuesday Wednesday

Fill out this check-in sheet as you go and use it to jot down any questions/issues that come up. Please check in with us along the way, we are here to help!6

-

What determines which registers are spilled to the stack by a trap function? ↩

-

What happens if the handler function does not clear the interrupt event? ↩

-

What (if any) is the consequence of not declaring the

gCountvariable asvolatile? ↩ -

Why might you want the handler to enqueue an update request and return instead of doing the actual task (e.g. redraw) directly in the handler? ↩

-

Are there any tasks you still need to complete? Do you need assistance finishing? How can we help? ↩

-

Do you have any feedback on this lab? Please share! ↩